Carbon Taxes vs. Emissions Trading Schemes (ETS): What’s the Difference?

As governments intensify their efforts to meet climate targets by assigning a cost to carbon output, carbon pricing has been raised as one of the most widely used policy tools to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. With these policies in place, national and international policymakers and regulators aim to internalize the environmental damage caused by emissions and steer economic behavior toward cleaner alternatives.

Although there are several forms of carbon pricing, two have emerged as the most dominant: carbon taxes and emissions trading schemes (ETSs). While both pursue the same objective, to reduce emissions at the lowest possible cost, economic approach and regulatory logics significantly differ. As more and more countries adopt and implement these rules, understanding how these systems work is becoming increasingly crucial for businesses.

Carbon Taxes: Definition, Scope, and Purpose

Carbon taxes directly set a price on GHG emissions, typically expressed as a fixed amount per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO₂e). The tax is applied to fossil fuels or emission-intensive activities based on the carbon content. As a result, pollution behavior is more expensive in a predictable and transparent way.

The main reasons policymakers value carbon taxes are their simplicity and price certainty. Equally important, businesses are aware of how much they will pay per unit of emission, which allows for more precise cost planning and long-term investment decisions.

While the basic concept is similar across jurisdictions, the scope of the carbon tax varies from one country to another. Some countries apply the so-called upstream taxation, taxing fuel producers and importers. Countries that have implemented upstream carbon taxes include Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, France, British Columbia (Canada), Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, and Uruguay, among others. In contrast, countries such as Singapore, Chile, and South Africa target final consumers or specific industrial sectors, applying downstream taxation.

Regardless of the concept and scope, revenues from carbon taxes are typically allocated to climate-related projects or are recycled back into the economy through tax reductions or household compensation measures. Although carbon taxes do not guarantee a specific level of emission reduction, they provide a stable price signal that encourages efficiency improvements and low-carbon innovation over time.

Emissions Trading Schemes and Their Role in Climate Policy

ETSs, or cap-and-trade systems, are the second-most common carbon pricing mechanism, setting a fixed limit, or cap, on total emissions within a defined scope. When implementing this form, regulators issue a limited number of emissions allowances, each representing the right to emit a certain amount of GHG. Businesses that fall under the scope of ETSs must surrender allowances equal to their verified emissions, but they are free to buy and sell allowances on the market.

The key feature of ETSs is emission certainty. More specifically, total emissions cannot exceed the cap, a predefined value, which is usually reduced over time in line with climate targets. The price of carbon depends on market trading, reflecting supply and demand allowance.

The ETS is designed to work so that emissions reductions occur where they are cheapest, promoting cost efficiency across the economy, at least in theory. In practice, allowance prices can be volatile, introducing uncertainty for businesses and potentially requiring regulatory interventions such as price floors, ceilings, or market stability mechanisms.

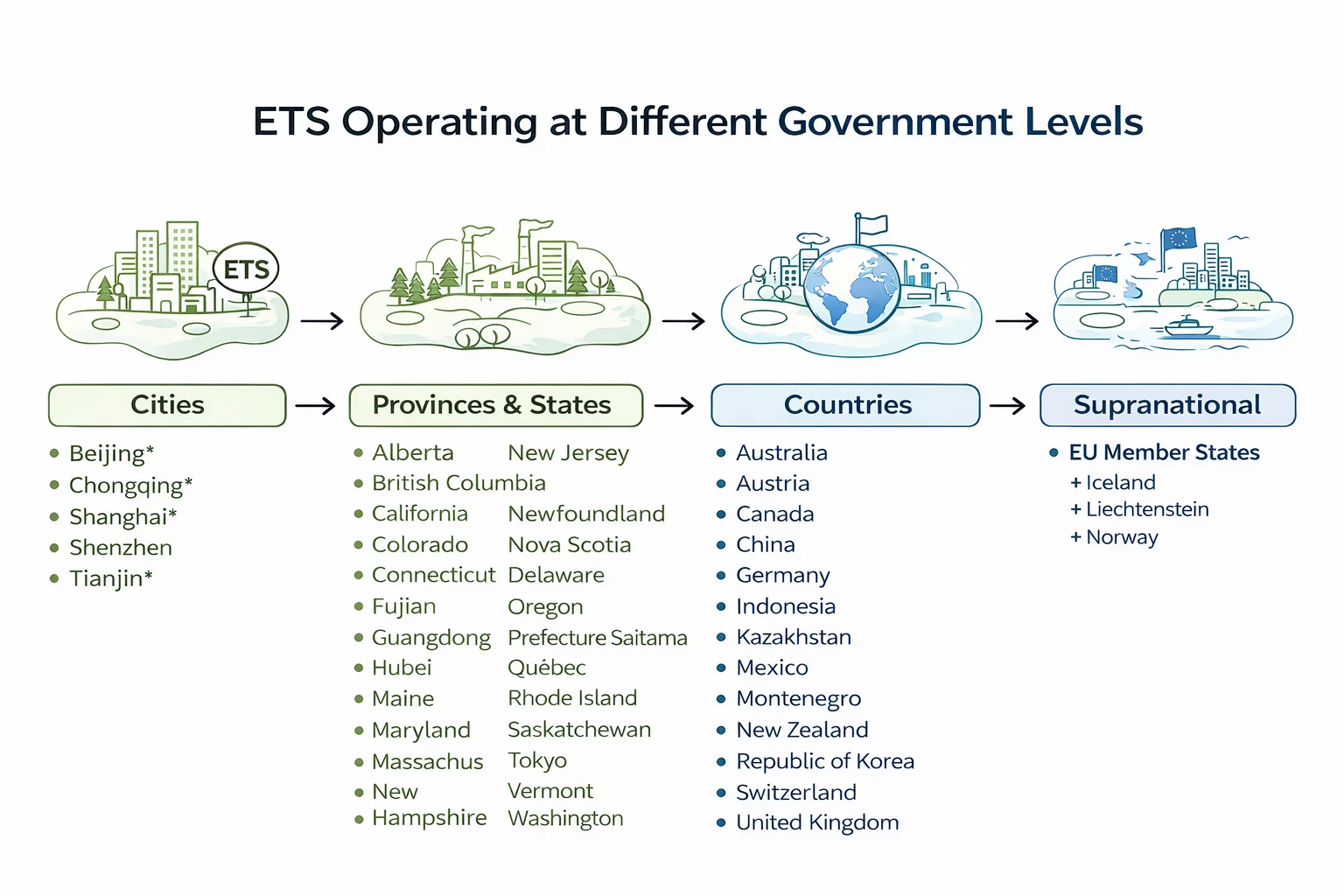

Currently, 38 ETS systems are in force, covering 12 GtCO₂e, which is 23% of global GHG emissions. In addition to these ETS systems, another 11 are currently being developed, and nine more are under consideration. From another perspective, nearly 33% of the world population lives under some type of ETS system.

* Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai, and Tianjin are provincial-level municipalities in the Chinese administrative system

Note: Data in the image is from the International Carbon Action Partnership Status Report 2025

Carbon Tax vs. ETS: Core Distinctions

The fundamental difference between carbon taxes and ETS lies in what each system directly controls. With a carbon tax system, governments control the price of emissions and leave the quantity of emissions uncertain. In contrast, an ETS system sets the amount of emissions and lets the cost fluctuate. This difference not only impacts policy design but also affects economic planning and business strategies.

However, the distinction between these two systems does not end here. From an administrative perspective, the carbon tax system is easier to implement and integrate into the existing tax system. This is particularly true for countries with strong fiscal institutions. ETS, on the other hand, are more complex and require robust monitoring, reporting, and verification systems. In addition, the ETS system requires market oversight to prevent manipulation and excessive volatility.

From a political point of view, carbon taxes can be more challenging to introduce due to their visibility. On the other end of the spectrum, although ETS can incur costs similar to or higher than those of carbon taxes, it is sometimes viewed as more flexible or market-friendly.

Notably, it is essential how businesses perceive these systems, and the costs and administrative burdens that come along with them. While carbon taxes offer predictability because of fixed costs per unit of emission, they have limited flexibility. By enabling the trade of emissions allowances, the ETS systems provide flexibility that allows businesses to optimize compliance strategies. Nonetheless, due to a lack of fixed pricing, ETS exposes businesses to price fluctuations that can affect profitability and investment decisions.

Evolving Carbon Pricing Systems: Hybrid and Transitional Systems

Depending on how you view it, either because of their flaws or their similarities, over time, the distinction between these two systems has become less rigid as policymakers increasingly experiment with hybrid and transitional systems.

Consequently, many ETS systems now include traditionally associated with taxation, such as price floors or reserve mechanisms designed to stabilize markets. Conversely, specific carbon tax systems incorporate performance-based exemptions, rebates, or sector-specific adjustments that introduce flexibility similar to trading systems. Thus, due to governments' efforts to transition from one system to another or to mitigate the downsides of each system, hybrid systems emerged.

These hybrid systems may include setting a carbon tax to establish a price signal, followed by the introduction of trading mechanisms as market infrastructure matures. Other systems may consist of multiple layers or instruments, for example, applying an ETS to large industrial emitters while using carbon taxes for transport or residential energy use. Nonetheless, one thing is sure: these systems are evolving to adapt to political constraints, economic conditions, and administrative capacity.

Note: Data in the table is from the 2023 United Nations Climate Change Regional Climate Week presentation

Conclusion

Overall, carbon taxes and ETS may be viewed as distinct but complementary approaches to carbon pricing. Even though they differ in structure, complexity, and economic impact, both serve to achieve the same goal: to reduce emissions by embedding environmental costs into market decisions. Notably, none of these systems is universally superior to the others. Essentially, the effectiveness of each depends on national circumstances, institutional capacity, and policy objectives.

Source: VATabout - Global Regulatory Landscape of Carbon Pricing Mechanisms, UNDP - Carbon Tax in an Evolving Carbon Economy: Policy Design & Digital Innovations, International Monetary Fund, International Carbon Action Partnership, European Commission - About the EU ETS, OECD, 2023 United Nations Climate Change Regional Climate Week

An ETS is a cap-and-trade system that sets a maximum limit on total emissions and allocates or auctions emission allowances. Companies must surrender allowances equal to their actual emissions, but can trade allowances on the market.

Carbon taxes directly control the price of emissions but not the quantity, whereas ETS systems fix the quantity of emissions and allow the price to fluctuate with market conditions.

Hybrid systems combine elements of carbon taxes and ETS, such as price floors in trading schemes or performance-based exemptions in carbon taxes, aiming to balance price stability and emission certainty.

Neither system is inherently superior. Their effectiveness depends on national circumstances, institutional capacity, economic structure, and the design and enforcement of the system.