What’s Next? Future Trends in Green Taxation

As we close the discussion on Carbon Taxes and Environmental Levies, it is necessary to consider what the future may hold for green taxes. However, one is already sure that what started as niche climate policy instruments has steadily expanded over the past decades into complex mechanisms that shape investment choices, influence corporate strategy, and reframe international trade dynamics.

Still, as with many other taxes and mechanisms, green taxation will undoubtedly continue to change. The question is which direction its scope, global coordination, mechanism design, and the treatment of carbon data are likely to evolve in the coming decade.

Broadening the Reach of Carbon Taxes and ETS

One of the defining trends in carbon pricing is the broadening scope of both carbon taxes and emissions trading systems (ETS) across sectors and jurisdictions. In its Effective Carbon Rates 2025 report, the OECD noted that the share of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions subject to carbon taxes or ETS coverage nearly doubled from 15% in 2018 to almost 27% in 2023, with more than 50 countries operating some form of carbon pricing instrument in 2023.

From all available data, it is apparent that ETS coverage, in particular, has driven much of this expansion, climbing from roughly 10% to 22% of emissions over the same period. The World Bank 2025 report on carbon pricing further demonstrates growth, stating that in 2025, 80 carbon taxes and ETSs were in operation worldwide, comprising 38 ETSs and 43 carbon taxes.

Nonetheless, the further expansion of existing systems is projected to increase global ETS coverage. One of the most notable examples was the Chinese government's national ETS expansion into heavy industry sectors such as aluminum, cement, and steel in 2025. Also, Brazil, India, and Turkey are planning to implement ETS, further underlining the development.

However, the number of countries with a carbon tax or ETS in place is not the only factor that might affect the development of these systems. As policymakers move beyond traditional sectors such as power generation and large industrial emitters to include road transport, international maritime transport, buildings, and even agriculture in carbon pricing frameworks, the coverage of these systems is also evolving.

Although explicit carbon pricing remains uneven across countries and industries, a trend toward making carbon costs more ubiquitous and reflective of real economic activity is apparent. The priority of policies is no longer just to reduce emissions but also to balance energy affordability, competitiveness, and revenue objectives.

Global Standards, Local Rules

A complex dialogue between global harmonization efforts and local regulatory diversity has accompanied the previously mentioned growth in carbon pricing coverage.

On one side, international institutions and organizations are striving to establish a common framework and facilitate policy alignment. In addition to the OECD and the World Bank, which play different but essential roles in this process, the International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP), a cooperative forum of jurisdictions with ETSs, is another significant player, as it fosters the exchange of best practices and technical cooperation among regional, national, and subnational programs.

On the other hand, the regulatory fragmentation remains a pressing challenge. Due to differing national or, in some cases, regional interests, differences in carbon tax rates, sectoral coverage, and compliance mechanisms remain key issues.

A notable example is the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The CBAM applies carbon levies on imports into the EU based on the carbon content of products to prevent carbon leakage and level the playing field for domestic producers. However, even though it is designed to incentivize stronger carbon policies abroad, CBAM could cause tensions with trading partners that view border adjustments as protectionist or discriminatory.

Given the criticism of existing systems, which could complicate international trade and investment flows, the likely path for green tax coordination lies in functional alignment rather than formal uniformity. The unified carbon pricing approach is expected to include shared reporting standards, mutual recognition of carbon pricing instruments, and collaborative frameworks that respect domestic policy autonomy while mitigating regulatory inconsistency.

Further Development of Hybrid Carbon Pricing Models

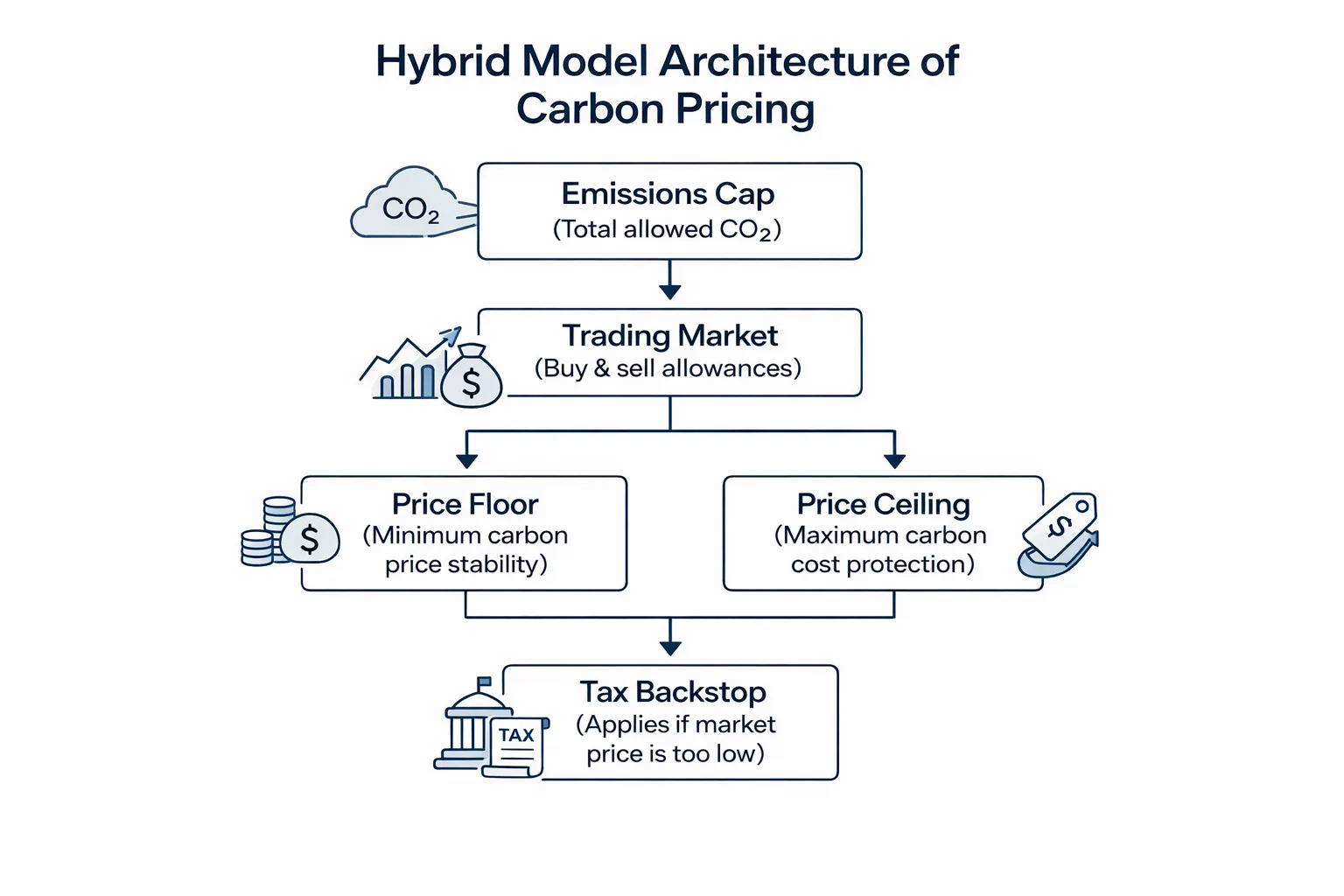

Throughout this series, we examined carbon taxes and ETSs both as distinct approaches to pricing carbon and as hybrid models that blend elements of both. As explained in the “Carbon Taxes vs. Emissions Trading Schemes (ETS): What’s the Difference?” article, hybrid models represent policymakers' attempts to adapt to political constraints, economic conditions, and administrative capacity.

One such example is Indonesia, which launched an ETS in 2023, initially covering large coal-fired power plants, with plans to implement a hybrid cap-tax-and-trade system with a carbon tax. In other words, Indonesia is integrating a carbon tax with ETS, a clear hybrid model.

With ongoing work on carbon taxes and ETSs, more hybrid models are expected to emerge. Moreover, given the need for a more unified global approach to this matter, hybrid models may be the solution needed to bridge the differences among existing rules and requirements.

Beyond Carbon: The Future of Environmental Levies

As already presented throughout this series, carbon taxes and ETS, although dominant, are not the only part of green taxation. Multiple environmental levies on other pollutants and resource uses, such as plastic gags, batteries, and packaging, are increasingly important. Moreover, the governments are exploring levies on water consumption and even biodiversity impacts to complement carbon pricing.

The measures examined and introduced around the globe aim to incentivize behavioral change and generate revenue for environmental projects, enforce circular economy principles, and address gaps in carbon-focused frameworks. Therefore, the evolution of environmental levies should further broaden the environmental pricing, that is, establish fiscal instruments to capture the economic cost of ecological harm beyond GHG.

For example, in 2023, the IMF noted that cryptocurrency mining presents a significant environmental externality. The IMF added that, even though voluntary green practices exist, effective corrective taxation or environmental crypto levy, either through carbon pricing or targeted energy-related taxes, is necessary to internalize these costs and reduce emissions. Examples of energy-related taxes include the US proposal to impose a 30% tax on miners’ electricity consumption and Kazakhstan's introduction of a similar tax with incentives for renewable energy use.

Conclusion

Considering the insights from this eight‑part series, one thing is clear: green taxation is no longer peripheral. On the contrary, it is a core factor of economic governance in the 21st century. Nonetheless, understanding the current rules and regulations and the future trajectory of environmental levies and carbon pricing is equally important for businesses to anticipate risks, seize opportunities, and design systems that deliver on the promise of compliance.

Source: OECD - Carbon pricing mechanisms are evolving, OECD - Effective Carbon Rates 2025, OECD - Tax Policy Reforms 2025, World Bank - State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2025, International Carbon Action Partnership, VATabout - Global Regulatory Landscape of Carbon Pricing Mechanisms, VATabout - Carbon Taxes vs. Emissions Trading Schemes (ETS): What’s the Difference?, VATabout - The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), VATabout - Environmental Levies in Practice: Plastic Bags, Batteries, Packaging, and More, IMF - Taxing Cryptocurrency

Coverage of greenhouse gas emissions subject to carbon taxes or ETS has nearly doubled in recent years, mainly driven by the rapid expansion of emissions trading systems across multiple jurisdictions, including China, Brazil, and India.

ETS frameworks offer greater flexibility, political acceptability, and market-based price discovery, making them attractive for governments seeking to balance environmental goals with economic competitiveness.

Beyond power generation and heavy industry, carbon pricing is increasingly extending to road transport, buildings, maritime transport, and potentially agriculture.

National economic structures, political priorities, and administrative capacities differ significantly, resulting in fragmented carbon tax rates, sectoral coverage, and compliance rules.

A fully unified global system is unlikely. Instead, functional alignment through shared reporting standards and mutual recognition of systems is the more realistic path forward.